A female salmon produces anywhere from 3,000 to 5,000 eggs.

A female salmon produces anywhere from 3,000 to 5,000 eggs.

There are seven species of salmon and trout in the Pacific and they have been around for seven million years – pink, chum, chinook, sockeye, coho, steelhead, and cutthroat trout.

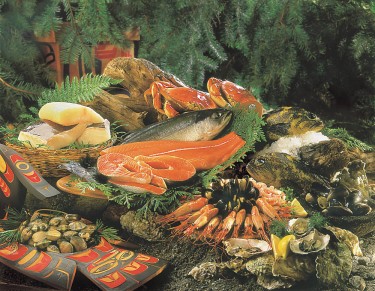

While eating more fish might seem like a simple, healthy dietary decision, in fact, it also offers consumers the chance to make a big difference to coastal communities in British Columbia.

While eating more fish might seem like a simple, healthy dietary decision, in fact, it also offers consumers the chance to make a big difference to coastal communities in British Columbia.

That’s the passionate belief of Jamie Alley, a former director with the B.C. Ministry of Environment, now retired and consulting to government, First Nations and the seafood industry.

“The seafood industry is not in sunset – in fact, it’s in sunrise,” he says. “Seafood is one of the most globally traded commodities. And considering the quality of the resource here, our industry is relatively underdeveloped.

Ironically, Alley says, even though the public sometimes fails to appreciate how valuable seafood really is, “it is the cornerstone of a lot of coastal communities.”

This is because B.C.’s oceans and fresh waters support more than 100 species of fish, shellfish and marine plants. With a combined current wholesale value of more than $1.4 billion, B.C. seafood travels around the world, with some 80 per cent of it being exported. In 2011, it ended up in two billion meals in 74 countries.

A key figure in working with industry to market the B.C. seafood brand for many years, Alley recalls travelling to Europe with the former executive chef from Vancouver’s C Restaurant, Rob Clark, to promote Pacific sablefish, or black cod. “At the time, we were selling 90 per cent of [the sablefish] catch to Japan and needed to diversify,” he recalls. “But at this event we had dozens of white-tablecloth, European chefs and global seafood traders lined up and down the aisles waiting to try one of the best fish in the world. “ As Alley puts it, marketing efforts like that, “help put money in the jeans of people in small rural communities.”

Sales of B.C. sablefish in Europe have increased dramatically since Alley’s trip, going from only $220,000 in 2007 to well over $3 million in 2012.

Alley believes that the secret to continued success is shifting from a high-quantity fishery with a low value – to a low-quantity fishery with a high value. Stories like the sablefish one have helped convince him that fish are more than simply a delicious food. They are also an economic engine for rural B.C.

According to Alley, jobs in the seafood industry in coastal communities are comparatively more valuable to the social and economic fabric of British Columbia than service sector jobs in the Lower Mainland.

“Seafood-industry jobs pay relatively well,” he says. These jobs tend to be located in smaller, coastal areas where overall unemployment rates can be high. Fisheries-related jobs, like those at seafood processing facilities, are particularly important for First Nations people, many of whom live in remote communities, far from urban centres. “There’s no other part of the coastal economy that has such a high participation of First Nations,” Alley says. First Nations people represent roughly 30 per cent of the workforce in the seafood-processing sector.

B.C. also has some of the best, most sustainably managed fisheries in the world. The global standard for seafood eco-certification, the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), has developed tough, best-practice standards for sustainable fishing and seafood traceability. The group’s mission? To recognize and reward sustainable fishing practices and thereby improve the health of the world’s oceans.

Six fisheries in B.C. are currently MSC certified and more are in the works. These are British Columbia chum, pink and sockeye salmon, albacore tuna, Pacific hake mid-water trawl, and Pacific halibut. In the MaPP study area, five fisheries are currently MSC certified – north and central coast chum salmon are in assessment. According to the 2011 British Columbia Seafood Year in Review, published by the B.C. Ministry of Agriculture, some 63 per cent of British Columbia’s groundfish harvest and 60 per cent of the salmon harvest was from MSC-certified fisheries. Overall, 47 per cent of B.C.’s wild capture fisheries harvest was from MSC-certified fisheries. Certified fisheries can use the eco-label program to market their products and influence the choices consumers make when buying seafood.

“B.C.’s seafood is healthy and sustainably managed,” says Alley. “You can buy it with confidence and support our fisherman to export it with pride to the world.”

Doug Neasloss was a kayak touring guide in the remote village of Klemtu, found on Swindle Island in B.C.’s Inside Passage (between Vancouver Island and southeast Alaska). Neasloss had just closed up shop for the 2003 season, when he got an unexpected visitor.

Doug Neasloss was a kayak touring guide in the remote village of Klemtu, found on Swindle Island in B.C.’s Inside Passage (between Vancouver Island and southeast Alaska). Neasloss had just closed up shop for the 2003 season, when he got an unexpected visitor.

“Then, this one lady showed up at my doorstep,” he recalls. “I explained that our season had ended but she got quite upset because she was a freelance photographer who’d flown here from Toronto.”

Neasloss checked the weather and agreed to take her out the next morning. He used his expert guiding knowledge to help her find a spirit bear, “and she got some amazing photos which allowed her to make a ton of money.”

This experience helped turn Neasloss into a photographer himself (he’s completely self-taught) and also sowed the seeds for what is now The Spirit Bear Lodge, a thriving eco-tourism business run by the Kitasoo/Xai’Xais First Nation.

The operation brings in about 300 visitors each year, many from Europe and Australia and employs 40 local people – mainly youth.

The heart of the enterprise? Interest in the region’s estimated 200 highly prized spirit bears. This majestically coloured white animal – that used to be, wrongly, thought of as a rare albino – is a sacred animal to the First Nations people.

Today scientists know that the spirit bear’s unique colouring is the result of a double recessive gene found in black bears. A white spirit bear can have a black cub and vice versa.

The spirit bear survives because of its isolation from other bears, namely grizzly bears, and an abundance of salmon in intact estuaries. These key characteristics are essential to Neasloss – and to the success of the lodge.

In fact, it’s one of the reasons he’s been so active in government-related work. A marine use planning coordinator for the Kitasoo Band from 2005 to 2011, he helped the community develop its own marine use plan. “We’ve been doing a lot of work on behalf of the bears,” he says, arguing that marine protection is just as important as land preservation. Why? Because bears depend on salmon.

Lodge manager Tim McGrady agrees. “If we’re not looking after the salmon, we’re not looking after the bears,” he says. “Without the salmon, we don’t have a business. The resources are at the core of what we do.”

The community is happy with the spectacular lodge it built in 2007 and looking forward to continuing to grow its business.

“We want to provide an alternative to the consumption economy,” says McGrady. “We couldn’t just be a small mom and pop business. We’ve had to show real revenue and real return. Logging and mining have been economic drivers in the region. We want to be a really viable alternative.”

A young Haida man is currently a training recruit at the Western Conservation Law Enforcement Academy in Hinton, Alberta. He will be the first ever Haida to act as a natural resource compliance and enforcement officer on Haida Gwaii.

Buster Bell, 35, was the best candidate, says May Russ, a Hereditary Chief and senior administrator for Council of the Haida Nation (CHN). “There were quite a few applicants but we were impressed that he’d done some RCMP training,” she says. “Hiring him was the next step in the Haida evolution as we work at managing the resources we have.”

Bell will be fully trained to Ministry of the Environment conservation officer service standards with all the associated responsibilities, including responding to complaints and investigating suspected legislative contraventions.

Enforcing rules about resources – in the most efficient and effective ways possible – is the key goal of a new integrated compliance and enforcement program taking shape on Haida Gwaii. The integrated team involves the B.C. Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations (FLNRO), Ministry of Environment, and the Council of the Haida Nation. They’re also working closely with Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve, National Marine Conservation Area Reserve and Haida Heritage Site staff.

Starting with land, and then moving to marine areas, the team hopes its efforts will result in a more integrated approach to compliance and enforcement for the islands. If things go well, this will also translate into saving money, says Leonard Munt, who is the district manager for FLNRO on Haida Gwaii.

“We’re trying to move from the tops of the mountains to the abyssal sea, even though we’re just learning to walk right now,” he says.

Noting that compliance and enforcement are complicated, Munt explains that one of the challenges the team faces is figuring out the cross-designation of the different jurisdictions. “Our ministry and the Ministry of the Environment have different authorities,” he says.

“One officer might not have the authority to address a particular issue. But if you’ve just spent thousands of dollars to put an officer in the field, you want him or her to be able to address every important issue.”

The same sort of rationale – figuring out how to share – also applies when it comes to equipment and supplies, such as trucks, boats and gas. Combine forces and you get more power. “To buy a boat costs $350,000,” Munt says. “Wouldn’t it be nice if we got all the teams to work together so that we could share all the assets? Then we’d have the right tools to do the right job with the right team.”

Munt notes that this kind of collaborative approach doesn’t work everywhere. It’s effective in this region because the land base is relatively small and because he’s working with just one First Nation with very clear boundaries. “But this is a solution that works well here,” he says.

The importance of this work is reinforced in Haida law. Under the Haida Constitution, the CHN is responsible for ensuring that Haida lands and waters are sustainably managed, continuing the traditional role of Haida watchmen who for thousands of years protected Haida Gwaii. Bell’s new position will strengthen the Haida capacity to achieve this, alongside ongoing marine monitoring and management activities fulfilled through the Haida Fisheries Program and Haida fisheries guardians.

For May Russ, it’s another step in the Council of the Haida Nation’s mandate to protect the Haida resource-based economy and lifestyle. Living on a small island, she particularly values the bounty of the sea. “It’s the basis of our food,” she says, “Not just the salmon, but also the halibut, the clams and the cockles are so important to our diet and to who we are.”

The Marine Plan Partnership for the North Pacific Coast (MaPP) introduces a refreshed website. New to the site is the Marine Planning Portal – a chance for you to explore a sophisticated marine planning tool with well over 200 data sets. Also check out MaPP Snapshots, a new section that offers stories of life, work, recreation, industry, culture, economic opportunity and biodiversity on B.C.’s North Pacific Coast.

The Marine Plan Partnership for the North Pacific Coast (MaPP) introduces a refreshed website. New to the site is the Marine Planning Portal – a chance for you to explore a sophisticated marine planning tool with well over 200 data sets. Also check out MaPP Snapshots, a new section that offers stories of life, work, recreation, industry, culture, economic opportunity and biodiversity on B.C.’s North Pacific Coast.

In addition, we have streamlined the site navigation, added more information and included many more photographs that capture the natural splendour, diversity and complexity of this vast marine area. Thank you to all the gifted photographers who have contributed their work.

When the MaPP draft marine plans are ready for public review, you’ll find all the information you need on our website about the draft plans and how to provide your input.

The site will continue to evolve over time as new information is available. For the latest information, please subscribe to MaPP updates and to the MaPP newsletter.

Back when Rick Snowdon was a full-time adventure guide he led an unforgettable trip with, among others, an Italian student who was soon to embark on his Ph.D. in nuclear physics.

“It was our last night,” Snowdon recalls. “We were waiting for the darkness so we could see the bioluminescence, and the student turned to me and said, ‘You know Rick, this has been the best week of my life.’”

There’s a word for the kind of high-end outdoors experience that Snowdon provides. It’s called glamping – a seductive blend of both “glamour” and “camping.” Customers of Spirit of the West Adventures – the company Snowdon co-owns – not only get to take adventure kayak tours in B.C.’s Johnstone Strait, they also enjoy the benefits of large tents with canopies, comfortable beds, high-end locally sourced food, and even hot tubs.

Some 55 per cent of Snowdon’s business is international, with the bulk of his customers coming from the U.K., Australia and New Zealand. The U.S. represents another 20 per cent and Canada captures the remaining 25 per cent.

Some 55 per cent of Snowdon’s business is international, with the bulk of his customers coming from the U.K., Australia and New Zealand. The U.S. represents another 20 per cent and Canada captures the remaining 25 per cent.

“Essentially, we’re producing an export product,” he says. “That’s an important point to consider when making comparisons to other industries.”

A believer in marine planning, Snowdon hopes the “zoning approach” – where different areas are dedicated to particular sectors, such as community/culture, general management and tourism – will allow individual groups to have sway in certain areas. “I hope tourism areas will be recognized for their usefulness,” he says.

When Snowdon talks about usefulness, he’s referring to an area’s ability to support growth, sustainably. One of the main tours his company runs is a base-camp style trip from Johnstone Strait. “That goes on as long as market conditions are favourable,” he says. Referring to viewscapes (or the vistas paddlers see while they’re kayaking,) he adds, “Our guests have high expectations. When they come to B.C. they want to see a natural product.”

Snowdon also makes the point that adventure tourism is an inherently sustainable business. Tourists will come back year after year, generating reliable income that, instead of disappearing as a resource is consumed, actually increases as a result of word-of-mouth.

He also concedes that tourism is harder for the government to manage. “Other industries have a few very large players with lots of revenues,” he says. “But tourism is much more diffuse. It’s a group of many, many small businesses that all work together to be part of a bigger whole. It’s harder for us to organize ourselves into a coherent voice.”

Still, thanks to his involvement as a North Vancouver Island Marine Plan Advisory Committee member for the commercial tourism sector, Snowdon has learned to listen to other voices. “I’ve come to appreciate that marine planning is a very long and involved process. I hope it guides future planning decisions.”

He has appreciated seeing First Nations and government relationships unfold. And he has learned to anticipate the needs of other sectors and work with them. “As much as we [tourism operators] sometimes feel we’re the underdog, we can’t take the position that [other industries] can’t do what they need to do,” he says.

“But I’ve also learned to be a stronger advocate for our needs.”

If biologist Janie Wray could persuade whale-watchers of any one principle, it would be this:

“Understand that while you’re having a whale experience, the whale is also having a human experience.”

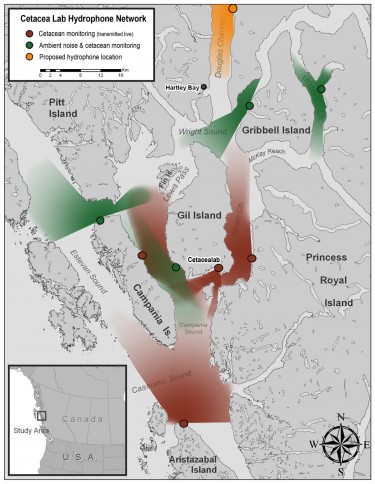

The co-director of the Cetacealab, a whale research facility on Gil Island, on the North Coast of B.C., is all too familiar with the mistakes that insensitive whale-watchers make.

“The greatest one is getting in too close with their boat,” she says. “The distance between the boat and the whale should be at least 100 metres. And once you get within 400 meters, you should be going very, very slowly.”

She suggests that tourists observe how whales interact with other whales, to get the right idea. “Whales always make their approaches very slowly,” she says, emphasizing that departures require the same protocol. “Quiet and slow. Whales perceive their environment through sound in the same way humans use sight.”

Wray and her partner Hermann Meuter have earned their knowledge of whales through years of observation. In the 1990s they worked at Orcalab, a land-based whale research station near Vancouver Island. In 2001, they established their current research station, Cetacea Lab, within Gitga’at territory on the North Coast.

Wray and her partner Hermann Meuter have earned their knowledge of whales through years of observation. In the 1990s they worked at Orcalab, a land-based whale research station near Vancouver Island. In 2001, they established their current research station, Cetacea Lab, within Gitga’at territory on the North Coast.

“Chief Johnny Clifton loved the idea of there being a whale research station in their territory,” Wray recalls when describing the early days in which she and Meuter had to camp, in the rain.

Now that the two have built their own facility, along with a place to live, they have eight listening stations set up throughout the area. Each station has a hydrophone – an underwater microphone – allowing them to record the sounds of whales, and just about anything else.

“We also hear fish grunts,” says Wray. “Or shrimps making clicking sounds. Or waves crashing on the shore. If it rains really hard we can hear the sound of rain, and we hear the disturbance of boat noise.”

The hydrophones, which can cost as much as $10,000, are set up to run on solar- and wind-power batteries.

A veritable encyclopedia of whale information, Wray says there are roughly 250 northern resident killer whales, 300 transient killer whales and about 2,000 humpbacks along the B.C. coast, with more than 300 whale observations recorded by Cetacea Lab. But the most exciting development for her has been the relatively recent appearance of fin whales.

“We didn’t see our first fin whale until 2006,” she recalls, “with only a few sightings per year until 2010.” Now, she’s lucky enough to see a fin whale almost daily and she remains awed by their impressive size – up to 70 feet long. This makes them the second largest animal on the planet, next to the blue whale.

A strong believer in marine spatial planning, and a member of the MaPP North Coast Marine Plan Advisory Committee, Wray says her involvement in this group has taught her the importance of listening to others, even those with conflicting views. Her role remains clear: by sharing her knowledge of whale distribution and behaviour, she wants to ensure that whales have good human experiences.

“This coast needs a voice,” she says, “and I think that all of these people coming together right now provide that voice.”

The Marine Plan Partnership for the North Pacific Coast (MaPP) announces the extension of the MaPP Initiative completion date from December 31, 2013 to June 30, 2014.

The Marine Plan Partnership for the North Pacific Coast (MaPP) announces the extension of the MaPP Initiative completion date from December 31, 2013 to June 30, 2014.

The MaPP Marine Working Group is pleased to report that marine plans are on track for completion within the original timeline. The additional six months is required to complete stakeholder, public and partner review of the draft plans and regional framework and to plan for implementation.

Once completed, the four MaPP sub-regional marine spatial plans and the regional framework will provide recommendations on marine uses and activities, marine protection and other key areas of marine management to inform decisions regarding the stewardship of British Columbia’s coastal marine environment.

We thank all the advisory committee members, stakeholders, partners, supporters and the MaPP planning team for their continued commitment to the MaPP Initiative and its successful completion.

MaPP Marine Working Group

Merv Child – Nanwakolas Council

Craig Outhet (Interim) – North Coast-Skeena First Nations Stewardship Society

Allan Lidstone – Government of British Columbia, Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations

Trevor Russ – Haida Nation

Spencer Siwallace – Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance

Garry Wouters – Coastal First Nations

Ecosystem-based management integrates human well-being, governance and ecological integrity

Planning based on best available ecological, social, cultural and economic information

Best available science supported by local and traditional knowledge

Marine planning that supports sustainable economic development and a healthy marine environment

A collaborative marine planning partnership between First Nations and the Province of British Columbia