DEVELOPING LOCAL EXPERTISE: Warren Bolton, a Kitsumkalum band member, GIS technician, and drone operator, undertakes eelgrass survey work near Ridley Island on the North Coast. Bolton’s involvement with MaPP’s CE project dovetailed perfectly with formal studies in the sciences. Photo credit: Quinton Ball

Marine plan implementation on the North Coast is getting a boost thanks to collaboration between the Marine Plan Partnership (MaPP) and the North Coast Environmental Stewardship Initiative (ESI) —a B.C. government initiative that was created to address First Nations’ environmental concerns around resource development.

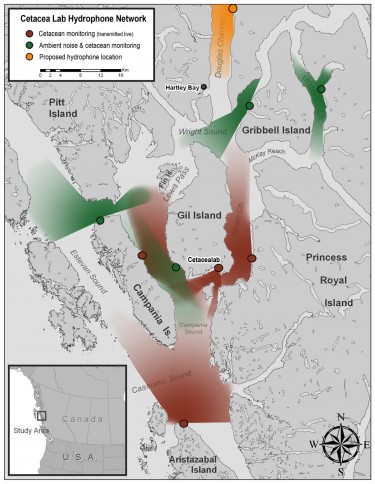

In 2017, the two groups informally merged into one team to accomplish a shared goal: Technically build out and fully implement a cumulative effects framework to monitor, assess, and manage the impacts of industrial and non-industrial development on the North Coast. Cumulative effects are the changes in environmental, social, economic, health and cultural values as a result of the combined effect of present, past and reasonably foreseeable human actions or natural events (MaPP, 2016). The project team includes representation from North Coast First Nations (Gitga’at, Gitxaala, Haisla, Kitselas, Kitsumkalum, and Metlakatla) and the Province of B.C.

A convergence of MaPP and ESI work on cumulative effects on the North Coast began in 2015. MaPP had already begun implementing its North Coast Marine Plan. Federal agencies (such as Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada) and provincial resource ministries (such as the Ministry of Energy, Mines and Low Carbon Innovation and the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development) were responding to the need for cumulative effects monitoring and deeper involvement of First Nations in decisions about coastal development projects—particularly, liquefied natural gas. With so many of the same people involved in related discussions, it made sense to bring them together.

Maya Paul, Program Director of Cumulative Effects Strategic Initiatives for the North Coast-Skeena First Nations Stewardship Society, co-manages the integrated MaPP and ESI North Coast Cumulative Effects Program. According to Paul, a key consideration for the North Coast Nations’ engagement in monitoring and assessment projects was their desire for the work to lead to decision-making and action. “North Coast First Nations knew cumulative effects were important but were approaching it independently. They knew they needed to work together, and with other governments, to achieve stronger and more meaningful outcomes.”

Team members are thoughtfully incorporating relevant learnings to support monitoring, assessment, and management of cumulative effects on core values of common importance. They’re currently focused on four values that were prioritised as a starting point: Aquatic Habitats (Estuaries, with a focus on the Skeena Estuary); Salmon; Food Security (with a focus on harvested foods); and Access to Resources (for social and cultural uses). Rebecca Martone, a provincial marine biologist on the North Coast Cumulative Effects project team, notes how important it is to assess interconnected indicators for the values they’re working on. “By developing and selecting indicators in parallel for habitats, key species, cultural values, and human wellbeing, we really start to understand the complexities in the methodologies required to assess cumulative effects, and how indicators can inform more than one value and thus create efficiencies for how those factors are considered in decision-making.”

MARINE BIODIVERSITY IN THE NORTH COAST: Abalone, otherwise known as sea snails, are a species at risk of extinction and are just one of many marine species that rely on healthy kelp forests in the North Coast. Photo credit: Maya Paul

Continued effort and dedication of team members has resulted in steady progress on each of the values. For example, a North Coast data management system has been developed to enable project team members to contribute, house, aggregate, analyze, and visualise a wide range of regional monitoring data to support decision-making. In addition to identifying a suite of indicators for the Aquatic Habitats (Estuaries) and Food Security & Access to Resources values, the Project Team has developed protocols that will set the procedures and standards for conducting assessments of the condition of the value now and in the future. They’ve developed a suite of indicators and implemented a survey to gather insights from North Coast First Nations community members on the Food Security & Access to Resources values. Quinton Ball, a Terrace-based environmental scientist contracted by Kitsumkalum Nation, explains: “Good indicators should serve as meaningful metrics that can be used to measure and understand change and enable affordable collection of standardised data that are useful for a variety of purposes.” Adds Ball, “Good indicators reveal important changes before we notice them.”

A current condition assessment of the Skeena Estuary value and a cumulative effects assessment of Food Security & Access to Resources values were completed in early 2021, which led to the development of a suite of interim recommendations that the team has begun to implement this year. A field monitoring project, designed to support assessment of the Skeena estuary, is now into its fifth year. The field program has realized many accomplishments, including training and engaging First Nations technicians in the marine environment, leveraging and building capacity in First Nations’ stewardship offices and improving the effectiveness of monitoring by utilising local knowledge in the design of the program. This has resulted in the collection of four years of data to serve as a beginning baseline for assessments. The team has also framed the scope of the initial assessment of the salmon value and began work on it at the end of 2020.

Heather Johnston, with the Environmental Stewardship Initiative Branch of the Ministry of Energy, Mines, and Low Carbon Innovation, co-manages the integrated Cumulative Effects program. She feels the project’s value extends far beyond the North Coast region. “It’s part of implementing the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, where First Nations have a real say in what’s going on in their traditional territories.”

Members of the North Coast Cumulative Effects Project team speak highly of each other’s qualifications and commitment to the work. “The level of professionalism and desire among agencies to collaborate—I just don’t think it’s been done at this level before,” says Ball. And Ball loves seeing new passions for science ignited among First Nations community members who get involved in monitoring work and then go on to explore science-related careers.

DEVELOPMENT IN THE NORTH COAST: Sustainable economic development in the North Coast is just one of the priorities being addressed through collaborative efforts between the Province of B.C. and several North Coast First Nations, through the Marine Plan Partnership (MaPP) and the North

Coast Environmental Stewardship Initiative (ESI). Photo credit: Maya Paul