NEWS RELEASE

For Immediate Release

2016FLNR0156-001388

Aug. 3, 2016

Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations

Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance,

Coastal First Nations-Great Bear Initiative

Council of the Haida Nation

Nanwakolas Council

North Coast-Skeena First Nations Stewardship Society

First Nations and Province sign marine plan implementation agreements

VICTORIA – Today, the Province and 17 coastal First Nations signed implementation agreements for four Marine Planning Partnership (MaPP) marine plans, collaboratively developed for the North Pacific Coast.

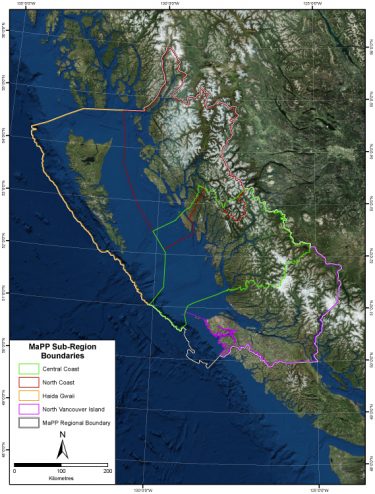

Completed in 2015, the plans foster a balance between stewardship and economic development using an ecosystem-based management approach that includes recommendations for marine management, uses and activities. Plans have been completed for four sub-regions: the Central Coast, Haida Gwaii, North Coast, and North Vancouver Island. In addition to the sub-regional marine plans, the Regional Action Framework, released this spring, outlines actions related to marine management that the Province and First Nations agree will be most effectively implemented on a regional scale. These actions are consistent with and support implementation of the sub-regional marine plans.

Taken together, these plans will inform First Nation and provincial decision-making in the respective sub-regional coastal and marine areas. The marine plans do not address management of uses and activities that the Province considers to be federal government jurisdiction. First Nations and the Province commit to working with the federal government on those issues.

In signing the implementation agreements, the partners agree to co-lead implementation of the marine plans, including ongoing engagement with communities, local governments, and stakeholders. The agreements describe how the Province and First Nations will work together and how implementation activities will be prioritized and managed. Example priorities include continuing collaborative governance arrangements; implementation of marine zoning; fostering marine stewardship, monitoring and compliance; and facilitating sustainable economic development opportunities to support healthy communities.

Implementation of the four marine plans will complement related plans and planning activities, such as the Pacific North Coast Integrated Marine Area Initiative, and the development of a Marine Protected Area Network for the Northern Shelf Bioregion, in addition to other MaPP partner initiatives within the sub-regions.

Quotes:

Steve Thomson, Minister of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations –

“I’m pleased that we are able to formally begin implementation of these important marine plans. These plans chart a long-term vision for our northern maritime areas and provide a useful set of recommendations to help facilitate the review, assessment and referral processes for marine use applications.”

John Rustad, Minister of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation –

“The implementation of these plans signals an important step forward in our efforts to improve relationships with First Nations on governance and management issues.”

kil tlaats ‘gaa, Peter Lantin, President of the Haida Nation –

“The Haida Gwaii Marine Plan is an important addition to the work the Haida Nation has completed on the land, working collaboratively with the Province for the well-being of Haida Gwaii. We look forward to working on the implementation of shared priorities that will sustain healthy oceans and an abundance of marine life for generations to come.”

Don Roberts, Chief Kitsumkalum Nation, chair of the North Coast-Skeena First Nations Stewardship Society –

“Implementation of the recommendations in the MaPP North Coast Marine Plan is a priority to the member and partner Nations of the North Coast-Skeena First Nations Stewardship Society. Signing this agreement means we will have a stronger working relationship with the Province of B.C. This will result in the protection of our resources and a healthy marine ecosystem.”

Doug Neasloss, governance representative, Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance –

“The Heiltsuk, Kitasoo/Xai’Xais, Nuxalk and Wuikinuxv Nations take responsibility for all the resources in our territories. While there is still much work to do to ensure our indigenous laws are reflected in all marine management decisions, working with the Province to implement the Central Coast Marine Plan represents an important step in our continued effort to ensure responsible stewardship and management in these areas. ”

Dallas Smith, President, Nanwakolas Council –

“The Nanwakolas Council is pleased to confirm an official implementation agreement with the Province that commits to our continued co-leadership in implementing the North Vancouver Island Marine Plan in our member First Nation territories. We jointly developed this marine plan with B.C. and signed it last year, on the condition of a formal implementation agreement. We now look forward to accelerating projects that will increase our governance and influence over marine uses and activities in our territories, as well as projects to achieve our goals for improved community economic health and ecosystem health.”

Kelly Russ, chair, Coastal First Nations – Great Bear Initiative –

“The implementation of marine plans ensures strategic, forward-looking planning for regulating, managing and protecting the marine environment. These plans include addressing the multiple, cumulative, and potentially conflicting uses of the ocean. The Coastal First Nations believe the marine plans are an important tool to balance existing and new ocean uses with protection, conservation and restoration of ecologically important ocean and coastal habitats.”

Learn More:

A backgrounder follows.

Media Contact:

Media Relations

Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations

250 356-5261

Russ Jones

Manager, Marine Planning

Council of the Haida Nation

250 559-4468

Ken Cripps

Program Director

Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance

250 739-0740

Robert Grodecki

Executive Director

North Coast-Skeena First Nations Stewardship Society

250 624-8614

John Bones

Marine Planning Coordinator

Nanwakolas Council

250 652-4002

Kelly Russ

Chair

Coastal First Nations – Great Bear Initiative

604 828-4621

Connect with the Province of B.C. at: www.gov.bc.ca/connect

BACKGROUNDER

Marine planning partnership regions

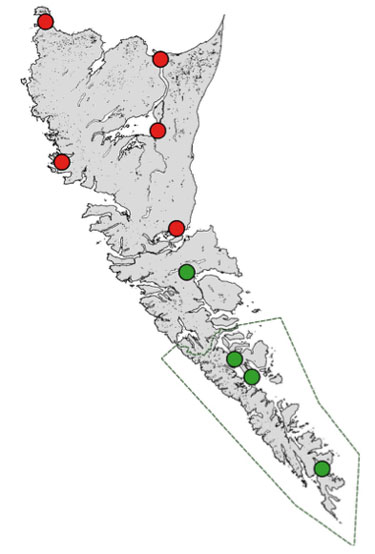

Central Coast Sub-Region

The Central Coast plan area extends from Laredo Channel and the northern tip of Aristazabal Island in the north to the southern limit of Rivers Inlet and Calvert Island. Moving from the west, the area includes the shelf waters of Queen Charlotte Sound, hundreds of islands, and exposed rocky headlands which meet an intricate shoreline in the eastern portion of the plan area. The shoreline is cut by narrow channels and steep-walled fjords that contain ecologically complex estuaries, calm inlets and pocket coves. Its main communities include Bella Coola, Bella Bella, Ocean Falls, Wuikinuxv, Shearwater and Klemtu. First Nations partners participating in the Central Coast Marine Plan include the Heiltsuk, Kitasoo/Xai’Xais, Nuxalk and Wuikinuxv Nations.

Haida Gwaii Sub-Region

Xaadaa Gwaay, Xaaydag̱a Gwaay.yaay, or Haida Gwaii (“Islands of the people”) is an archipelago on the edge of the continental shelf off the north coast of British Columbia. It is surrounded by several large bodies of water – Hecate Strait separates Haida Gwaii from the mainland, and the islands are bounded by Dixon Entrance in the north, Queen Charlotte Sound to the south and the Pacific Ocean to the west. The chain of islands extends roughly 250 kilometres from its southern tip to its northernmost point and includes the communities of G̱aaw (Old Massett), Masset, Gamadiis Llnagaay (Port Clements), Tll.aal Llnagaay (Tlell), Hlg̱aagilda (Skidegate), Daajing Giids (Queen Charlotte) and K’il Llnagaay (Sandspit). Boundaries for the Haida Gwaii plan area are defined by the Haida Statement of Claim (east/south), the international boundary with the United States (north), and the toe of the continental slope (west). Gwaii Haanas is included in the Haida Gwaii sub-region but spatial zoning for this area is being addressed through a separate planning process.

North Coast Sub-Region

The North Coast plan area includes an impressive stretch of coastline that is indented with deep fjords and dotted with thousands of islands. It is a region of profound beauty, significant ecological diversity and remarkable cultural richness. The North Coast plan area extends from Portland Inlet to the south end of Aristazabal Island, where it has an overlap with the northern boundary of the Central Coast plan area. The western edge of the North Coast plan area borders the Haida Gwaii plan area. Prince Rupert, Terrace and Kitimat are the largest communities in the North Coast plan area, and support an overall population of approximately 42,000 people. Participating First Nations in the North plan area include the Gitga’at, Gitxaala, Kitsumkalum, Kitselas, Haisla, and Metlakatla Nations, who are represented by the North Coast-Skeena First Nations Stewardship Society, in this planning process.

North Vancouver Island Sub-Region

The North Vancouver Island plan area is home to the Kwakw’ka’wakw First Nations and lies between northern Vancouver Island and B.C.’s mainland. There are many islands, inlets and fjords within the area, which is characterized by its natural beauty and biodiversity of species and ecosystems. Major water bodies include Queen Charlotte Sound, Queen Charlotte Strait, Johnstone Strait, Smith Inlet, Seymour Inlet, Knight Inlet and Bute Inlet. The plan area includes the communities of Port Hardy, Port McNeill, Alert Bay, Sayward and Campbell River. Members of the Nanwakolas Council and partners in the MaPP initiative are: Mamalilikulla-Qwe’Qwa’Sot’Em, Tlowitsis, Da’nakda’xw-Awaetlatla, Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw, Wei Wai Kum, Kwiakah and the K’ómoks First Nations.

Media Contact:

Media Relations

Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations

250 356-5261

Russ Jones

Manager, Marine Planning

Council of the Haida Nation

250 559-4468

Ken Cripps

Program Director

Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance

250 739-0740

Robert Grodecki

Executive Director

North Coast-Skeena First Nations Stewardship Society

250 624-8614

John Bones

Marine Planning Coordinator

Nanwakolas Council

250 652-4002

Kelly Russ

Chair

Coastal First Nations – Great Bear Initiative

604 828-4621

Connect with the Province of B.C. at: www.gov.bc.ca/connect