Kelp bed in the North Vancouver Island sub-region. Credit: Nanwakolas Council.

The giant and bull kelp plants that grace British Columbia’s waters are not only beautiful to look at; they are important indicators of the province’s coastal ecosystem health. First Nations Guardians are part of the vital and exciting work taking place to learn more about them.

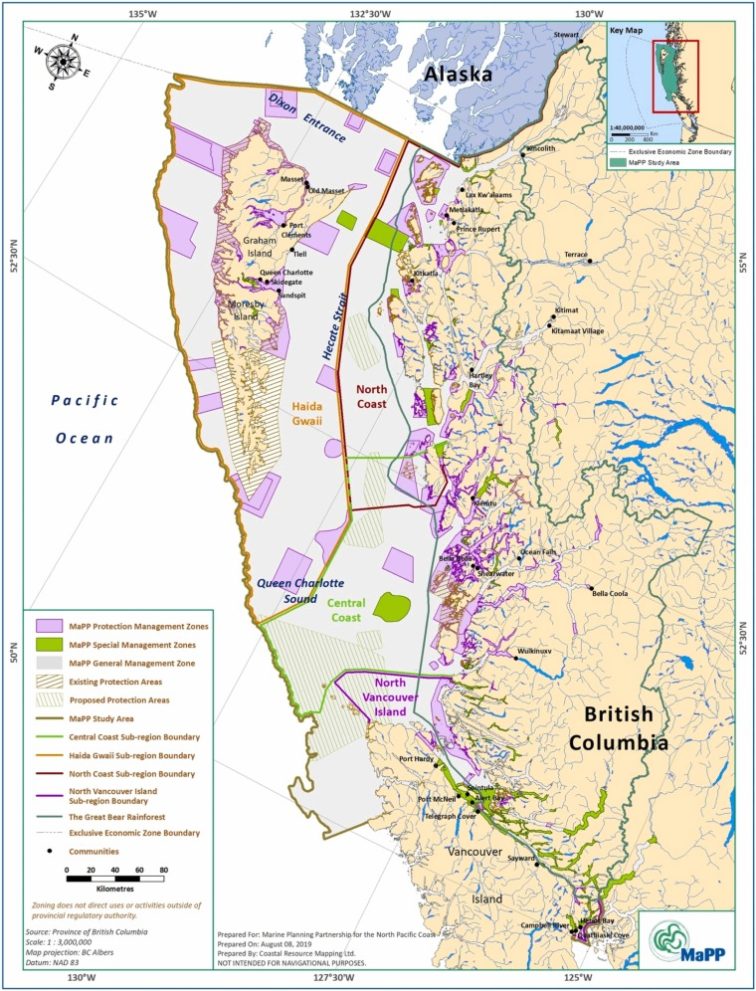

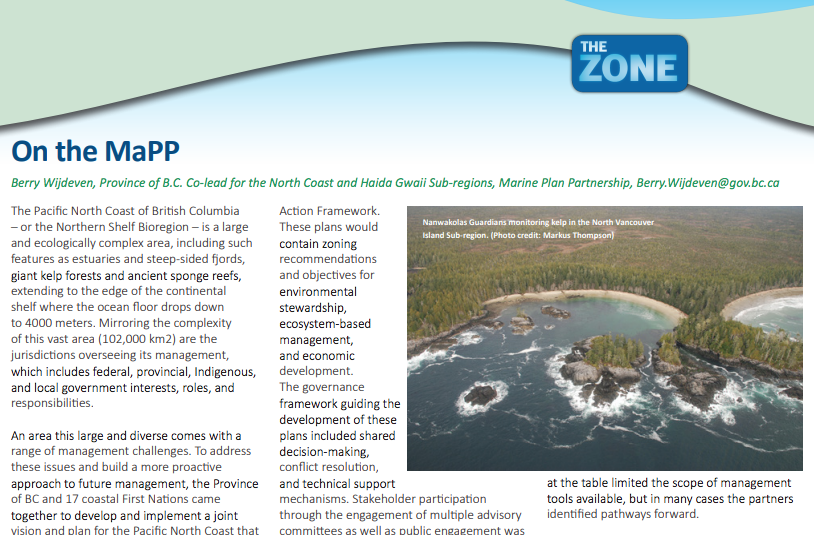

“Some of the areas we are studying are incredibly biodiverse,” enthuses Markus Thompson. Thompson, a marine environmental practitioner based on Quadra Island, has been working over the 2018 season with First Nations Guardians, staff from Nanwakolas Council, the provincial government, and the Hakai Institute on the first phase of a study of kelp in the waters around Northern Vancouver Island. The project was initiated and supported by the Marine Plan Partnership for the North Pacific Coast, or MaPP for short.

“Nutrient rich waters and strong currents along the northeastern coastline of Vancouver Island support a huge abundance of wildlife—whales, sea lions, and of course, kelp. But each First Nation territory also comes with unique challenges. Some territories have such an abundance of kelp that we have been unable to survey all of it,” says Thompson. “There’s a lot more to be done to ensure we have the right information to make sure we’re taking good care of these precious ecosystems.”

What’s the deal with kelp?

Thompson worked closely on this project with provincial government marine biologist Dr. Rebecca Martone. Martone, who works for the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development (FLNRORD) describes her role this way: “My primary responsibility is supporting the implementation of the MaPP marine plans and the marine protected area network process.” The bigger picture, she explains, is supporting ways to “get good science into decision-making,” from an ecosystem-based management, or EBM, perspective.

Monitoring indicator species like kelp is an important part of planning and implementing an EBM framework, say both experts. “If you think about the objectives of EBM being effective ecosystem function and human well-being, healthy marine habitats support that,” explains Martone. “An EBM indicator program is about measuring the status of systems like marine habitats and the things that affect them, so we can manage them most effectively to meet those objectives.”

Rebecca Martone and Markus Thompson provided kelp monitoring training to Guardians. Credit: Nanawakolas Council.

Kelp, as it happens—both the giant and the bull species that grace most of British Columbia’s coastline—are excellent indicator species of marine habitat health. “If the kelp isn’t thriving, it’s likely that whatever is causing that is also affecting other parts of the ecosystem negatively. Moreover, kelp are the foundational species that support many other ecologically, culturally, and economically important species, so the loss of these habitats can have cascading effects. Understanding the status of the kelp is going to be very helpful in assessing the overall health of the region,” says Martone.

Trouble is, we don’t know what we don’t know

Aquatic plant harvesting is regulated by FLNRORD, which licenses the wild harvest and culture of aquatic species and commercial harvesting. Kelp is used commercially for everything from herbal remedies to cosmetics and fertilizer, and for medical purposes. First Nations harvest kelp on which herring have spawned, as well as for general consumption.

But the last time any studies were undertaken of these important species was in 2007, in one small part of the central coast. Scattered studies of small areas have been undertaken since the mid-1970s, but no comprehensive contemporary inventory of the coast as a whole exists.

Filling that information gap is important, says Thompson, for three reasons. Firstly, understanding the state of the species can, as we know, tell us a lot about the overall health of the marine environment on British Columbia’s coast. “Secondly, we have an opportunity to work closely with First Nations this time to undertake the monitoring and include their knowledge in the assessment of species health. Last but not least,” says Thompson, “there’s been a flurry of recent applications to harvest more kelp, but we don’t have up-to-date information on the health of the kelp stocks to inform decisions on those applications.”

The goals of the study are to bring up-to-date measurements of data like water temperature and salinity together with observations and analysis of both human activity and other

influences such as climate change, to assess impacts on and changes in the ecosystem over time. “For example,” says Thompson, “kelp productivity is generally most productive in cooler water, so as water temperature increases with climate change we may see a drop in kelp abundance. Another example is that we are seeing sea otters returning to the east coast of Vancouver Island. Sea otters eat sea urchins, which eat kelp, so that will have an impact as well.”

Guardians travel to kelp monitoring sites. Credit: Nanwakolas Council

Not least of all the study project, which began in 2018, will incorporate invaluable First Nations’ knowledge. “It’s a great fit,” says Martone. “It’s pretty challenging to monitor species that are mostly underwater, in remote locations with difficult access. Having people who know the territories inside out, who are competent in boats in these places and who understand how the tides work and the tough conditions is priceless.”

Western scientists, adds Martone, are only “beginning to understand” the value of traditional knowledge and experience. “These perspectives are not less valuable, simply different, to the way other science has looked at the issues.” Science, she says, is observational by nature, and about wanting to understand what’s happening. “So there’s a major connection to local knowledge and experienced local interpretation of what we are seeing.”

Working in partnership with First Nations

“Eelgrass was originally identified as the regional indicator species to study but in discussions with the First Nations, kelp came up as a priority as well,” notes Martone. “They told us that’s because they have been observing major declines in abundance, particularly on the north coast and around Vancouver Island. They are very concerned about the increased interest in harvesting kelp under the circumstances.”

Working with First Nations Guardians who have significant experience and knowledge of the environment and who are comfortable working in remote, challenging waterscapes, but who also don’t necessarily have a scientific qualification, demanded a partnership approach to the design of the study that was scientifically rigorous but practical and straightforward. “An important part of this work is building the capacity within the First Nations to undertake the monitoring work directly,” says Thompson. “So we designed the approach together in the best way to achieve that.”

Tier Two kelp surveys are conducted from kayaka. Credit: Markus Thompson

Getting out on—and into—the water

The team took a three-tier monitoring approach to the study project. “In tier one, we just wanted to know how much kelp there is, and where it is,” says Thompson. “The best way to do that was to go out in small boats with the Guardians, who know where to find the kelp, and a GPS system to map locations and extent of the kelp beds, and then spend a few minutes in each bed making notes about what you could see from the surface, the density, visible impacts, any other species in the beds like urchins or sea otters nearby.”

Based on the data gleaned from tier one, tier two surveys were done in a two-pronged approach: from kayaks and through drone aerial imagery. More detailed information about the extent, density and biomass of the kelp beds was gathered from this method of surface observation. Over hundreds of kilometres of coastline, the Guardians patiently counted kelp bulbs and strands in quadrants of one square metre at a time. At the same time, a start was made on gathering overhead images of the beds using drones. Tier three continued the work underwater, using scuba divers to observe what is happening below the surface.

All three tiers were deployed in 2018, says Thompson, with divers for the tier three work supplied by the Hakai Institute and the A-Tlegay Fisheries Society.

Preliminary findings confirmed that the distribution and density of kelp across all of the regions substantially different, and a relationship exists between bull kelp stipe diameter and biomass, among other things. In 2019, the work will continue, again taking on all three tiers. The partners will continue working together to refine the approach and find ways to improve the field testing methods, as well as how the data obtained will feed into longer-term planning and ecosystem management, including harvesting controls.

Tier Three surveys are conducted underwater by divers. Credit: Ryan Millar

Putting power in the hands of the First Nations

An important element will be continuing to work with the Guardians to increase their capacity to undertake the monitoring work themselves, including training and qualifications in underwater work. “I think this is one of the biggest benefits of this work so far,” says Thompson. “It’s so important that the First Nations have access to this information to inform their decisions about taking care of their territories based on our collective knowledge and work.”

Thompson also notes, that requires commitment on the part of the non-First Nations partners to stay the course: “You can’t just parachute in and then stop,” he says firmly. “We have to commit to the relationship and seeing through the work, and that isn’t completed when these short-term studies are finished. That’s a long-term commitment.”

Fortunately, that seems to be the collective view. “Working with the Guardians has been such a gift for me,” says Martone. “Their knowledge is so critical to the work we do together. The fact they have invited me out on the water and shared their perspectives with me is incredibly rewarding. I hope they feel the same way!”

The long view

Gina Thomas, senior Tlowitsis Guardian, certainly does.” I think this work is going to be very helpful,” says Thomas. “It’s also been very helpful to connect directly with the decision-makers in the province. That’s been a really exciting part of this year’s experience.” Thomas says you also have to take a long-term view: that in the bigger picture, it is all about managing the kelp and the ecosystems for better health and the well-being of all concerned.

When you get out on the water with people from the government and other partners First Nations work with, says Thomas, and everyone sees what it is like in these beautiful, remote places, “we find we share the same passions and desires for good outcomes for them. We have the same information, we’re on the same page, and it makes it easy to make good decisions.”

Gina Thomas monitors kelp. Credit: Nanwakolas Council