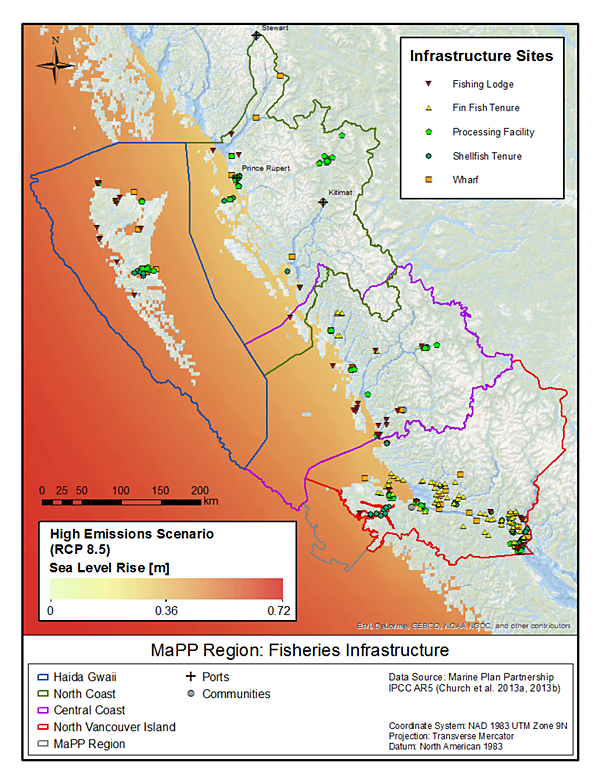

MaPP’s new Regional Climate Change Assessment study offers a bird’s-eye view of current projections of how climate change will play out across MaPP sub-regions. This map – one of dozens in the report – shows locations of First Nations fishing infrastructure in relationship to regional variations (up to 72 cm by the end of this century) in sea-level rise under a “high” scenario of global emissions. Source: “Regional Climate Change Assessment: Projected Climate Changes, Impacts and Recommendations for Assessing Vulnerability and Risk across the Canadian North Pacific Coast.”

A recently completed MaPP study provides the clearest picture yet on how climate change is poised to affect communities and ecosystems.

Titled “Regional Climate Change Assessment: Projected Climate Changes, Impacts and Recommendations for Assessing Vulnerability and Risk across the Canadian North Pacific Coast,” the study was completed in February 2018 by Charlotte Whitney and Tugce Conger, Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions fellows and PhD candidates from the University of Victoria’s School of Environmental Studies and UBC’s Institute for Resources, Environment, and Sustainability.

To do it, Whitney and Conger systematically examined hundreds of peer-reviewed scientific publications and studies undertaken by government, private firms, and environmental non-government organizations. To get a sense of work in progress, they also interviewed other key researchers in B.C. about relevant, ongoing projects.

“I was surprised by how much work has been done, but just not always consistently across the region,” Whitney says of the process. “Pulling it all together like this showed there is a lot we can use to make better management decisions at multiple scales, and a lot of actions that can be really effective in supporting communities within the MaPP region in coming years.”

The resulting 135-page synthesis affirms that site-specific changes to ecosystems on the B.C. coast are already underway now, and will deepen in coming decades. Air and ocean surface temperatures will continue to rise, as will sea levels—averaging about 20 to 30 cm by 2100. Ocean water will become less salty, more acidic, and lower in dissolved oxygen. Winds, waves, storms, flooding, and extreme weather events are expected to become more intense. Snowmelt will keep happening earlier and faster, making for more intense freshets (the sudden rise of water level in a river due to melting snow or ice) and hotter, drier summers in some regions.

The researchers expect these phenomena to have far-reaching effects on the ecosystems, economies, and cultures of MaPP communities. For example, the geographic ranges of key species of salmon, herring, shellfish, and crustaceans may shift. Communities and critical marine infrastructure will be more vulnerable to sea-level rise and extreme weather events. Many cultural sites, valuable in their own right but also as proof of historical First Nations presence, will be more vulnerable to erosion and loss; though the vulnerability will vary across the sub-regions. Pollutants that have been stored in glacial ice for centuries will be released as glaciers melt, potentially impacting habitat.

One unique aspect of this study—and in line with its intent—is that it drills down into existing data to explore how climate change will play out over the coming decades at regional and sub-regional scales. For example, it indicates that the northeast coast of Graham Island, Haida Gwaii, is especially sensitive to sea-level rise, but that warmer and longer summers may also bring new opportunities in tourism. On the Central Coast, MaPP communities are less vulnerable to sea-level rise than other regions, but have a greater proportion of documented cultural sites at risk and can expect a major decline (32%-49% decline by 2050) in herring—a key source of food, income, and cultural practice.

The study’s appendices offer a treasure trove of practical information. For example, readers can look up key species in a table that lists the climate change factors they are vulnerable to and how they are likely to be affected. A set of colour-coded maps illustrates communities’ varying sensitivities, under different emissions scenarios, to factors such as changing salinity and sea-level rise.

Equally useful is the study’s highlighting of locally relevant but still unanswered climate-change questions—such as the impacts of ocean acidification, and the ways that warming waters, by harbouring new marine diseases and invasive species, will change marine ecosystems. These unanswered questions will help guide future climate change research.

During the research, Whitney and Conger invited feedback from key MaPP team members—like Rebecca Martone, a Victoria-based marine biologist with B.C.’s Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development.

“This study really helps us to put the puzzle pieces together in a way that hasn’t been done before,” enthuses Martone, who is on the MaPP technical team. “It helps us identify where we have more certainty in projected impacts, so we can prioritize actions to take, and where we need more information. And it really strengthens the scientific foundation for the work of MaPP.”

For John Bones, First Nations co-lead for MaPP implementation in the North Vancouver Island sub-region, the study offers strong motivation for proactive effort. “The most valuable insight from this study for First Nations communities … is probably that climate change impacts on ocean characteristics—like salinity and water temperature—are going to affect ocean-based cultures and traditions,” he reflects. “Each community needs to start developing an ‘action plan’ for both the threats and opportunities that might result.”

Whitney agrees, and emphasizes the wisdom of framing community conversations less in terms of vulnerabilities and more around communities’ adaptive capacity—“the latent potential of people and ecosystems to adapt”—and proactive planning. To that end, the researchers included recommendations for high-level planning principles and an appendix about adaptation measures that communities can start taking now.

“Building on initiatives that are already involving communities in planning, management, and capacity development—like the Guardian Watchmen program—would be really valuable,” adds Whitney. “It could turn this into a story about potential.”

As the MaPP team prepares to share study findings with MaPP communities, Whitney and Conger have gone on to complete a second, complementary literature review, which evaluates frameworks and tools for carrying out vulnerability and risk assessments for the MaPP region—work that will be undertaken next year.

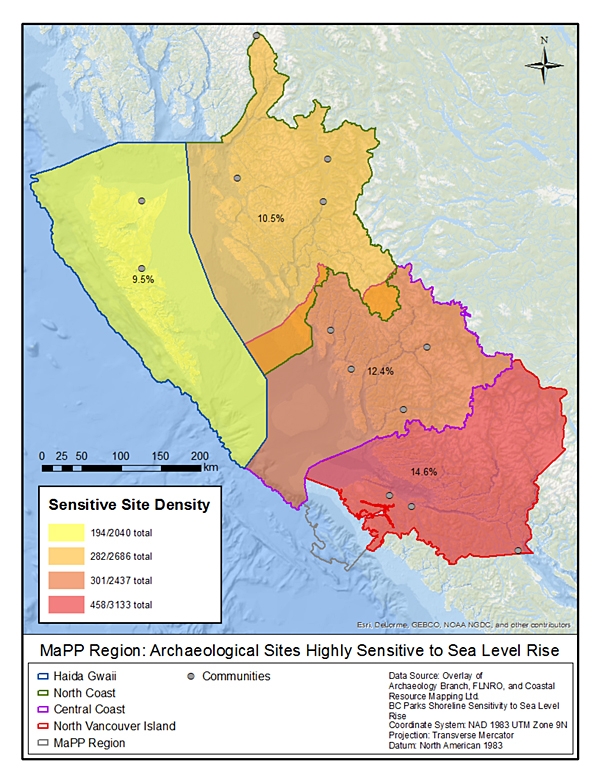

Rising sea level and increased storm surge can subject archeological sites to erosion or inundation. This map shows that some MaPP regions are more vulnerable to this than others. The North Vancouver Island sub-region, for example, has the highest proportion of its documented archeological sites at risk.

Source: “Regional Climate Change Assessment: Projected Climate Changes, Impacts and Recommendations for Assessing Vulnerability and Risk across the Canadian North Pacific Coast.”

Report Citation: Whitney, Charlotte, and Tugce Conger. 2019. “Northern Shelf Bioregion Climate Change Assessment: Projected Climate Changes, Sectoral Impacts, and Recommendations for Adaptation Strategies Across the Canadian North Pacific Coast.” MarXiv. May 3. marxiv.org/rfnk3.

Read the report online here.