Kayakers in Xaana Kaahlii (Skidegate Inlet) Photo by Shayd Johnson

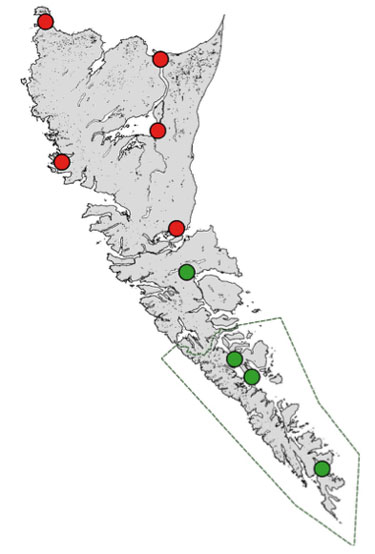

Each year, ecotourism brings recreational kayakers from all over the world to the spectacular shores of Haida Gwaii, with many poised to visit Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve, Marine Conservation Area and Haida Heritage Site in the southern half of the archipelago. However, through implementation of the Marine Plan Partnership (MaPP), the Council of the Haida Nation (CHN) and Province of British Columbia (BC) are exploring ways to encourage and manage respectful marine tourism in other locations around Haida Gwaii. One example is the development of a marine trail (or kayak route) in Xaana Kaahlii Skidegate Inlet, a narrow channel between the archipelago’s two largest islands that effectively splits Haida Gwaii’s landmass in half.

The stunning and diverse landscapes and marine life of Xaana Kaahlii provides ample opportunities for accessible day trips for entry-level paddlers as well as challenging multi-day adventures by more experienced kayakers. However, there are currently limited resources, infrastructure and management measures to support kayakers to plan trips safely and sustainably. Over recent years, MaPP partners have worked with BC Marine Trails to identify opportunities and management needs of kayak sites within the area with the aim of developing a kayak route that mitigates cultural, ecological or social harm while promoting safety and sustainability.

“The inlet offers world-class kayaking,” said Cameron Dalinghaus, BC Marine Trails’ First Nation Liaison, “but it is also full of culturally and ecologically sensitive sites and has been an area of significance for Haida people for time immemorial. We need to balance the preservation of these sites so that visitors access them in ways that are respectful.”

Kayakers in Xaana Kaahlii (Skidegate Inlet) Photo by Marty Clemens.

Indigenous Nations have worked for decades on communicating proper protocol to visitors of their territories, however, Cameron acknowledges that some tourists still assume they are allowed to go wherever they want. He says a model of visitation is needed that respects Indigenous governance and management of territories, and that cultural awareness needs to be top of mind for visitors.

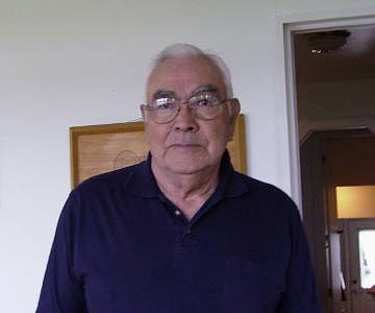

Gaahlaay Lonnie Young, Hereditary Chief of the K̲aayahl ‘Laanaas clan, who’s territory includes parts of Xaana Kaahlii, speaks to his community’s hesitation with Haida Gwaii’s growing popularity among visitors; pointing specifically to past disrespect tourists have shown to Haida villages such one of his clan’s villages in Xaana Kaahlii, Xaayna Llnagaay:

“In the past, visitors came to Xaayna and removed significant artifacts, even headstones from the graveyard. Experiences like that sour some of our people about letting others go there,” said Gaahlaay. “We have reservations about ecotourism because we know operators cannot police their clients all the time. We’d like to show people what happened at Xaayna. It would be educational for visitors to witness what was done without consultation or permission. Having watchmen at the village would allow the clan to support the kayak route. I’m all for people coming and visiting if they are respectful, [but] trust has to be earned.”

Together, the project partners have worked with local paddlers to develop a list of potential sites that may be part of the route and are consulting with Haida knowledge-holders and subject-matter experts to identify and assess cultural, archeological and ecological sensitivities within the area. Management strategies are being developed collaboratively, grounded in respectful and responsible stewardship.

This project also aims to amplify local initiatives for visitors to follow Haida laws and values during their stays, such as the Haida Gwaii Pledge and Visitor Orientation. The partners will continue to work on site and route planning in the coming months, with expectation to start rolling out guidelines for kayaking in Xaana Kaahlii ahead of the 2024 tourism season.