Eelgrass is a good measure of coastal health because it is both ecologically important and sensitive to its environment, said Karin Bodtker, a manager at the Coastal Ocean Research Initiative. Eelgrass grows in estuaries throughout the MaPP region. In this photo, two locals harvest seafood from an eelgrass meadow in Haida Gwaii. Photo credit: Nusii Guijaaw.

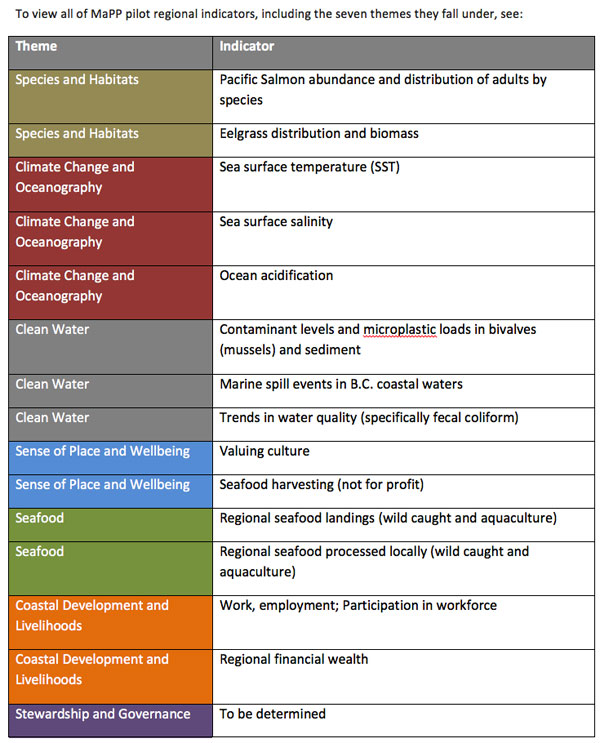

The Marine Plan Partnership for the North Pacific Coast (MaPP) has picked 14 pilot regional indicators that, taken together over the long-term, will provide insights into the health of B.C.’s North Pacific Coast and help guide implementation of coastal management recommendations in MaPP sub-regional plans.

Hundreds of potential ecological, economic and human well-being indicators were initially identified by experts at Uuma Consulting and planning team members of the four MaPP sub-regions: Haida Gwaii, the North Coast, the Central Coast and North Vancouver Island.

To select the pilot indicators, MaPP partners and the Coastal Oceans Research Institute (CORI) took feedback from sub-regional workshops and focused on indicators considered high-priority within each sub-region and which made sense to track at a regional scale. As indicators can be expensive and time-consuming to monitor, the team chose indicators that would each provide unique insights without incurring excessive costs.

“It was challenging to narrow the list down,” said MaPP regional projects coordinator, Romney McPhie. “There are many things that are valuable to track, but collectively we came up with a short list that all sub-regions agreed upon to start the monitoring process.”

Eelgrass, the ribbon-like seagrass in estuaries throughout the region, was one of the indicators selected. MaPP personnel will track data on eelgrass distribution and biomass regularly during the 20-year implementation period of the MaPP plans.

“Eelgrass is one of the most ecologically important habitats. It’s also quite sensitive to pollution, sedimentation, sea level rise and even boats anchoring in it,” said Karin Bodtker a manager with CORI, the independent research institute based at the Vancouver Aquarium, that helped refine the list of indicators with MaPP.

“This plant provides habitat for about 80 per cent of marine species of commercial interest,” Bodtker explained. “Juvenile salmon, for example, use eelgrass habitat to find food, hide from predators and as a highway in their migration out to the ocean.” Eelgrass also captures and stores carbon.

Understanding eelgrass losses or gains, alongside changes to other indicators like ocean acidity, will help MaPP understand the state of the marine environment and how it is changing over time. “The information collected will support sustainable decision-making along the coast,” said McPhie.

Indicators are to be monitored from the middle of Vancouver Island through to the Alaskan border. They fall under seven themes: marine species and habitats; climate change and oceanography; water cleanliness; sense of place and wellbeing; seafood; coastal development and livelihoods; and stewardship and governance. These indicators reflect the MaPP commitment to ecosystem-based management, which prioritizes ecological integrity, human wellbeing and collaborative governance. In keeping with an adaptive approach, certain indicators may be changed if compelling reasons to do so arise, McPhie said.

In addition to the pilot regional indicators, sub-regions will have their own unique indicators for which they gather data. The Central Coast, for example, is monitoring crab and Haida Gwaii is monitoring the spread of invasive species, such as tunicates.

With regional indicators chosen, data collection is now underway. An analyst at CORI is assembling existing data on many indicators and identifying sampling gaps.

“This program couldn’t happen without many other organizations that are collecting data: governments, private organizations, the coastal guardian watchmen and the regional monitoring system of the Coastal First Nations, for example,” McPhie said. “We’re ensuring we have reliable data through our collaboration with CORI, as well as through data access agreements we hope to secure with other governments and organizations.”

MaPP partners are also now developing data management tools and public reporting strategies.

“By the end of 2019 we expect a comprehensive report with regional data for all the pilot indicators and how those data relate to MaPP strategies. Analysis of the data will tell us if our strategies are working and if we need to change our strategies because of ecosystem changes,” McPhie said.

“The purpose of indicator monitoring is to lead to better decision making. The Province can use the data to set or affirm priorities, allocate resources and inform policy and decision making,” said Kristin Worsley, manager of B.C.’s marine and coastal resources section and member of MaPP’s secretariat.

Steve Diggon, regional marine planning coordinator for Coastal First Nations-Great Bear Initiative said, “Provincial decision-makers and First Nations will have evidence to inform their views on and decisions about issuing tenures for coastal activities.”