If biologist Janie Wray could persuade whale-watchers of any one principle, it would be this:

“Understand that while you’re having a whale experience, the whale is also having a human experience.”

The co-director of the Cetacealab, a whale research facility on Gil Island, on the North Coast of B.C., is all too familiar with the mistakes that insensitive whale-watchers make.

“The greatest one is getting in too close with their boat,” she says. “The distance between the boat and the whale should be at least 100 metres. And once you get within 400 meters, you should be going very, very slowly.”

She suggests that tourists observe how whales interact with other whales, to get the right idea. “Whales always make their approaches very slowly,” she says, emphasizing that departures require the same protocol. “Quiet and slow. Whales perceive their environment through sound in the same way humans use sight.”

Wray and her partner Hermann Meuter have earned their knowledge of whales through years of observation. In the 1990s they worked at Orcalab, a land-based whale research station near Vancouver Island. In 2001, they established their current research station, Cetacea Lab, within Gitga’at territory on the North Coast.

Wray and her partner Hermann Meuter have earned their knowledge of whales through years of observation. In the 1990s they worked at Orcalab, a land-based whale research station near Vancouver Island. In 2001, they established their current research station, Cetacea Lab, within Gitga’at territory on the North Coast.

“Chief Johnny Clifton loved the idea of there being a whale research station in their territory,” Wray recalls when describing the early days in which she and Meuter had to camp, in the rain.

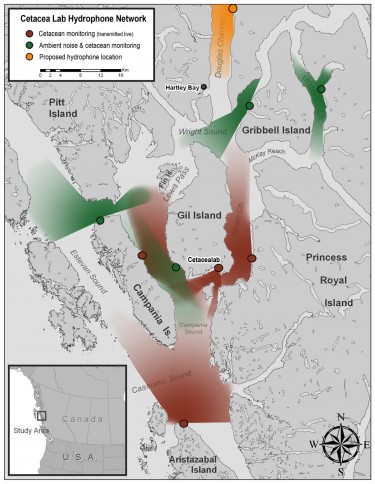

Now that the two have built their own facility, along with a place to live, they have eight listening stations set up throughout the area. Each station has a hydrophone – an underwater microphone – allowing them to record the sounds of whales, and just about anything else.

“We also hear fish grunts,” says Wray. “Or shrimps making clicking sounds. Or waves crashing on the shore. If it rains really hard we can hear the sound of rain, and we hear the disturbance of boat noise.”

The hydrophones, which can cost as much as $10,000, are set up to run on solar- and wind-power batteries.

A veritable encyclopedia of whale information, Wray says there are roughly 250 northern resident killer whales, 300 transient killer whales and about 2,000 humpbacks along the B.C. coast, with more than 300 whale observations recorded by Cetacea Lab. But the most exciting development for her has been the relatively recent appearance of fin whales.

“We didn’t see our first fin whale until 2006,” she recalls, “with only a few sightings per year until 2010.” Now, she’s lucky enough to see a fin whale almost daily and she remains awed by their impressive size – up to 70 feet long. This makes them the second largest animal on the planet, next to the blue whale.

A strong believer in marine spatial planning, and a member of the MaPP North Coast Marine Plan Advisory Committee, Wray says her involvement in this group has taught her the importance of listening to others, even those with conflicting views. Her role remains clear: by sharing her knowledge of whale distribution and behaviour, she wants to ensure that whales have good human experiences.

“This coast needs a voice,” she says, “and I think that all of these people coming together right now provide that voice.”