With a 158 mm-wide carapace, this European green crab (Carcinus maenas) trapped by the CCIRA monitoring team is unusually large: on the Central Coast, the observed average is closer to 50 mm. Females can release up to 185,000 eggs once or twice per year, and larvae can drift around 50 to 80 days in ocean currents before settling to the sea floor. Image courtesy of CCIRA.

Four First Nations are partnering with the Province of B.C. to implement MaPP on the Central Coast through a coordinated response to three aquatic invaders: European green crab, tunicates, and bryozoa.

Originating in northern Europe, green crab is billed by Fisheries and Oceans Canada as “one of the world’s 10 least wanted species.” They’re small (about 10 cm wide) but multiply rapidly, tolerate a wide range of salinities, and survive out of the water for up to two weeks. They disrupt ecosystems by voraciously consuming mussels and clams and decimating habitat for important species like Dungeness crab, wild salmon, and manila clams.

Tunicates (commonly known as sea squirts) and bryozoa (tiny aquatic invertebrate animals) are at least as pernicious. These filter-feeders live on almost any underwater surface, including plants, other animals, and marine structures. Growing in colonies, they can quickly overtake kelp and seagrass beds, plug water pipes, and sink marine structures. Once established in a new area, they’re very tough to get rid of.

Tristan Blaine is a professional diver and field technician who works for the Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance (CCIRA, which is comprised of the Heiltsuk, Kitasoo/Xai’Xais, Nuxalk, and Wuikinuxv First Nations). He describes the challenge of “biofouling” from tunicates and bryozoa: “You clean them off [marine structures], and a month later they’ve totally regrown. The amount of work involved is pretty concerning.”

Keith, a Guardian Watchman from the Nuxalk Nation who is engaged with the CCIRA monitoring effort, retrieves a green crab trap. These traps are relatively costly, imported from Japan, and specially designed to minimize bycatch—provided they’re checked almost daily. Image courtesy of CCIRA.

These problematic species have hitchhiked to oceans around the world, as larvae in ballast water on intercontinental shipping routes and on poorly cleaned boat hulls, fishing gear, aquaculture equipment, floating debris, and ocean currents.

In May 2017 as part of MaPP implementation, CCIRA began building on the Heiltsuk Nation’s work over the past decade to eradicate green crabs around Gale Creek—by expanding it to include the other Central Coast Nations. More than 10 people (Guardian Watchmen and other fieldworkers) from the four Nations are now monitoring these aquatic invaders, collecting critical baseline data on their presence, abundance, and damage to the ecosystem.

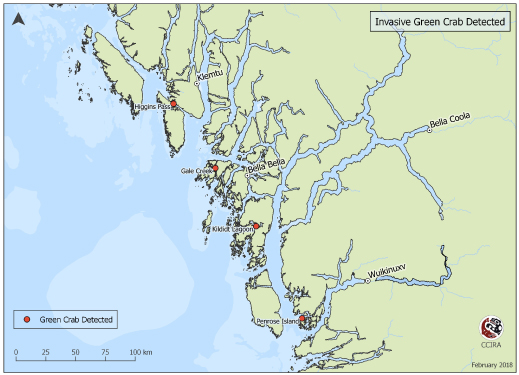

For green crabs, the monitors use traps specially designed to reduce bycatch, boating several times weekly to trap locations to record trap data and dispatch them (usually by freezing). Green crab have been found at 4 of 25 continuously sampled sites—but data suggest green crab are spreading more slowly than expected on the Central Coast. Is this because of Heiltsuk extirpation efforts—destroying hundreds annually—or because of deep, chilly conditions of the region’s many fjords?

“We don’t know yet,” says Blaine. “But I can guarantee that if more trapping effort were all that’s required to get rid of green crab, these Nations would have everyone in their communities helping.”

This translucent tube-shaped species of tunicate, Ciona savignyi, is one of many now appearing on the Central Coast. This filter-feeder consumes small organisms like phytoplankton, zooplankton, and the larvae of important species of fish and shellfish. Growing in colonies, it can reach a height of six inches and rapidly outcompete local species. Image courtesy of CCIRA.

To look at tunicates and bryozoa, monitors suspend weighted plates 1.5 m below docks at Shearwater Marina—about 4 km east of Bella Bella and the hub of Central Coast marine traffic. “The goal is to sample areas with highest boat traffic, because that’s one of the ways they spread,” explains Blaine.

After five months, monitors retrieve plates, record data on the observed tunicates and bryozoa in CCIRA’s database, and send five randomly selected plates to researchers at Fisheries and Oceans Canada for detailed analysis.

The intent was to quickly train local stewardship technicians to do all baseline analysis, but it’s a very specialized process. There are only a few biologists in BC equipped to definitively identify these invasive species, using a microscope and working through complicated classification steps. Each of the 22 1-cm2 points on a plate can host several tunicate and bryozoa species, and analysis of five plates can take a couple of days to complete.

This map shows the locations where invasive green crab was detected in the Central Coast sub-region. Image courtesy of CCIRA.

Data shared among Nations begs questions: If eradication of invasives isn’t realistic, can they be contained? Should regulations be strengthened and better enforced, and if so, how? How will climate change affect these introduced species?

Some answers may come from a related MaPP-funded study on climate change that began in January at the University of Victoria, says Sally Cargill. She’s a marine planning specialist with the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development, and is the provincial co-lead on implementation of the Central Coast marine plan.

“They’re looking at existing frameworks and tools for carrying out vulnerability and risk assessments that have been used around the world,” says Cargill, noting that risks include invasive species. “They’ll recommend assessments that could be applied to the MaPP areas.” The sub-regions could then decide to carry out detailed vulnerability and risk assessments in coming years—which could lead to actions such as additional monitoring, site restorations, education campaigns, and measures to protect aquaculture operations.

The Nations’ millennia-long connection to these ecosystems is integral to this work, says Blaine: “They rely on the surrounding resources to survive, and a big priority for these communities is to make informed choices about resource management.”